Girls attending this year’s Women In Aviation conference, held in Long Beach March 14-16, are each receiving a copy of a book about one of Long Beach’s famed women aviators, Barbara Jane “BJ” Erickson London, courtesy of a donation by Aeroplex/Aerolease Group. London’s daughter, Terry Rinehart, hopes the donated books and the conference itself will inspire young attendees to pursue careers in aviation like she and her mother did.

Rinehart was the first woman pilot for Western Airlines, hired in 1976. London was also a pioneer as a woman in aviation: she was one of the first Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) hired in anticipation of World War II, during which time she became commander of the WASPs operations at Long Beach Airport.

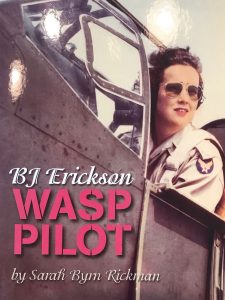

“BJ Erickson, WASP Pilot,” by Sarah Byrn Rickman, chronicles London’s experience in the WASPs. Her story began in the 1930s, when the United States government started a program at universities to train pilots in anticipation of becoming embroiled in World War II. Only 10 women were allowed in the program at each school, Rinehart said. At the University of Washington, London was one of them.

“As the war progressed, they still didn’t have enough pilots to try to move the planes that were coming off the assembly lines,” Rinehart said, referring to the U.S. military. As a solution, the military hired women pilots to transport airplanes. This ensured that as many male pilots as possible would be freed up to fight abroad. Women weren’t allowed in combat.

“My mom was the commander of the base in Long Beach. She had 60 women beneath her. They flew everything the military had,” Rinehart reflected. “My mother was the only woman during World War II who was awarded the Air Medal,” she noted, referring to a military recognition awarded for meritorious flight achievement.

After the war, London, like all other women, was not allowed to stay in the military. Nor were women allowed to fly for commercial airlines, Rinehart noted. London went to work selling aircraft at a couple of Long Beach companies before starting a business, Barney Frazier Aircraft, with a partner. She didn’t retire until her 80s, Rinehart noted. London passed away in 2013.

Rinehart comes from a family of pilots – her father, husband and all three of her children are pilots. But when Rinehart was coming up in the industry in the 1970s, there were few women in commercial aviation. “When I got hired, there were probably less than 10 women flying for airlines throughout the United States,” she said.

Rinehart said that while her airline was well-run, she did encounter sexism on the job. “Now, it’s much more common to see a woman in the cockpit. But there were still a lot of males who felt that this was their environment and we were infringing on that. We did kind of what we needed to do to get along to go along,” she explained. “Back in the day you just didn’t make a big fuss over somebody making sexist comments. Nowadays, you wouldn’t put up with things like that. But back then we heard many times on the radio [things] like, ‘Another empty kitchen,’ or ‘Who’s taking care of your kids?’” she recalled.

“Unfortunately, since I got hired in 1976, the percentage of women pilots hasn’t really expanded too much. We’re still somewhere between 4-6% of the airline pilot population,” Rinehart said, adding that becoming a pilot is a lengthy, costly process. That’s why the Women In Aviation organization each year hosts a girls’ day as part of its annual conference – to encourage young women not only to consider becoming pilots, but also to explore other careers in aviation, according to Rinehart. This year’s girls’ day is Saturday, March 16.

Girls flying in to the Long Beach Airport to attend the conference will travel down Barbara London Drive before exiting onto Lakewood Boulevard, Rinehart noted.

“Girls between 10 and 18 can come for $10 a day and learn about all kinds of jobs in aviation,” Rinehart said. “Curt Castagna of Aeroplex at the Long Beach Airport is donating 250 of my mother’s books to every single girl who comes to this convention to try to inspire them to reach a little bit higher and understand women who have gone before them.”

To learn more about the conference, visit wai.org/events/2019-international-women-aviation-conference.