Japanese car manufacturer Toyota is planning to bring a fuel cell power plant to its Port of Long Beach facility, making it the company’s first fully renewable operation, according to Craig Scott, director of the Advanced Technologies Group for Toyota Motor North America. For the project to come to fruition, Toyota and its partner in developing the plant, FuelCell Energy, need buy-in from the local utility, Southern California Edison (SCE). But SCE has refused.

Toyota’s operations at the Port of Long Beach process approximately 200,000 vehicles every year, with cars produced in Japan coming ashore to be purchased by U.S. consumers and those produced in Baja California and Kentucky boarding ships destined for countries around the globe. “That port facility is our largest port facility outside of Japan,” Scott told the Business Journal. “It’s a very important part of our business.”

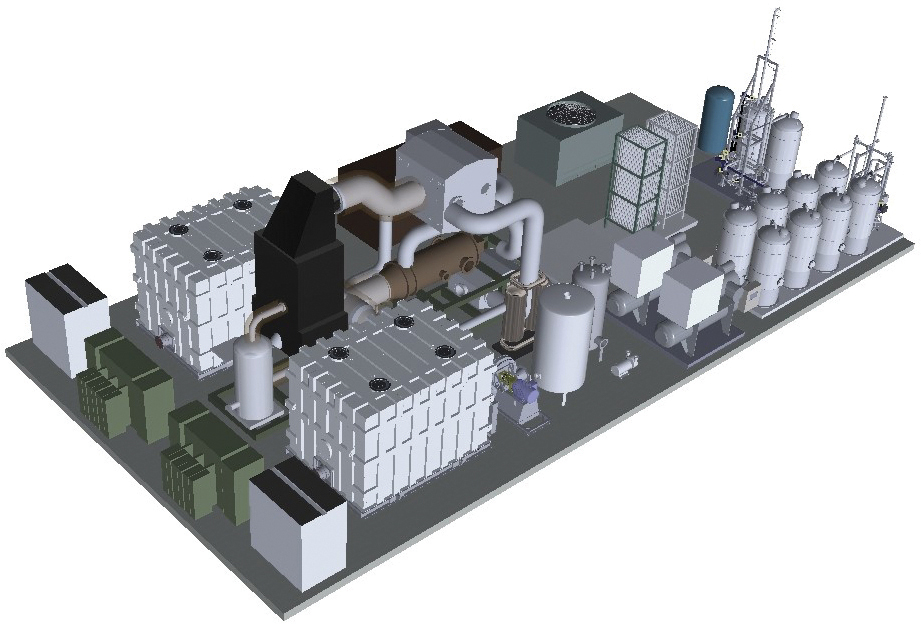

Together with the Connecticut-based technology firm FuelCell Energy, the car manufacturer is planning to add a hydrogen fuel cell power plant to its 130-acre facility at the port. The plant would produce energy, hydrogen and water from directed biogas, part of which would be used to power local operations, fuel a new fleet of hydrogen trucks and rinse off vehicles at the on-site car wash.

But despite receiving its stamp of approval from the Long Beach Board of Harbor Commissioners in August 2018, work on the 2.3-megawatt plant has been halted. The reason? The plant would produce far more power than necessary for Toyota’s local operations, which FuelCell plans to sell to the local utility, SCE, as a way of recovering its investment in the facility. But SCE is clutching its coin purse.

FuelCell, a publicly traded company that reported total revenue of $89.4 million in 2018, produces, installs, operates and maintains megawatt-scale fuel cell systems, serving utilities as well as industrial and large municipal power users. In California, FuelCell stands to benefit from a program designed to increase the portion of renewable energy in the state’s power mix. The Bioenergy Market Adjusting Tariff (BioMAT) is a feed-in tariff program, which allows eligible plants to sell power to one of the state’s three investor-owned utilities at a fixed price that’s significantly higher than that of power produced from non-renewable sources. And that’s where the issue lies.

SCE would have to accept the new plant into its BioMAT program to ensure its profitability. The utility has refused to do so, according to a May 22 letter sent to the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) by Doug Murtha, Toyota North America’s group vice president of strategy and planning. “While this project is critical to Toyota’s and California’s clean energy goals and has garnered wide-ranging support, its future is now in imminent jeopardy given what Toyota understands has been SCE’s unwillingness to date to confirm the project’s eligibility under the BioMAT program despite clear precedent,” Murtha wrote in the letter.

SCE spokesperson Robert Laffoon Villegas said he couldn’t comment on the Toyota project specifically, but told the Business Journal that SCE’s concerns focus on the type of fuel used to power the plant, which is commonly referred to as directed biogas.

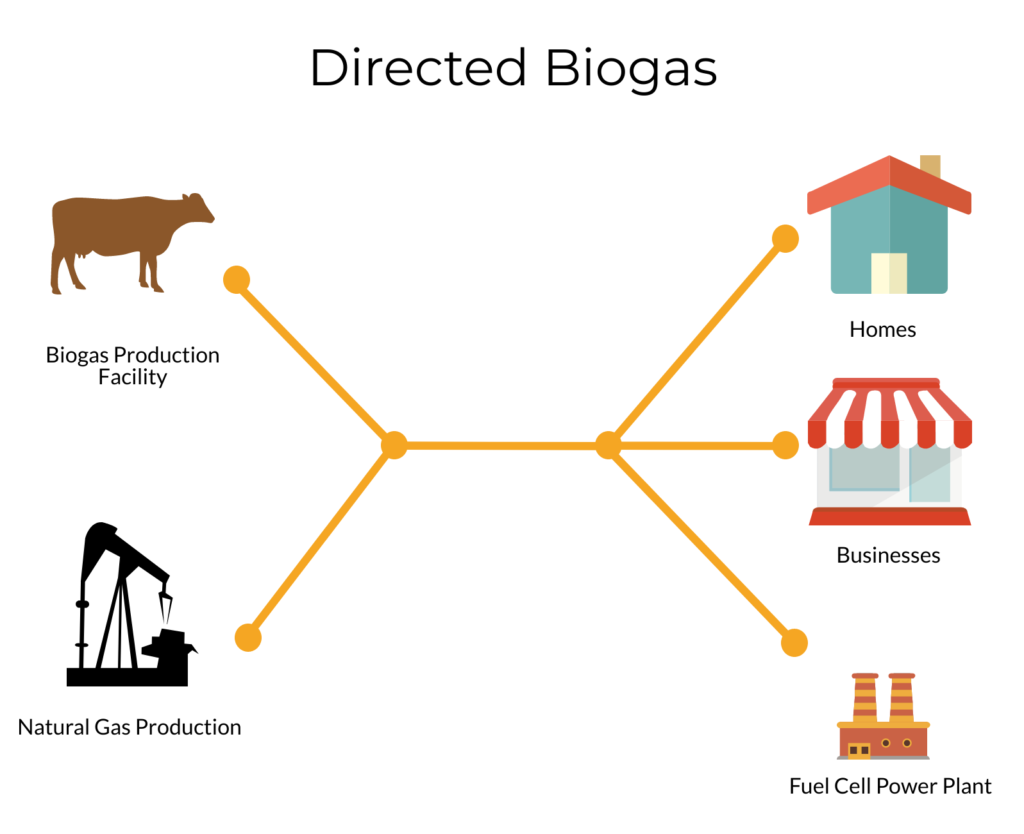

Biogas is produced from biomass, commonly collected from agriculture or sanitation. In urban and suburban environments, sanitation districts’ wastewater treatment facilities often supply the biomass necessary to produce fuel. In rural areas, dairy farms are a common source.

Directed biogas describes the procurement of biogas from an off-site facility, which is then pumped into the general gas pipeline, where it mixes with traditional natural gas. While FuelCell’s plant wouldn’t be using the exact molecules pumped into the pipeline by its biogas supplier, the project would increase the portion of renewable gas in the pipeline system, FuelCell and its partner Toyota argue. “Because the plant would be purchasing renewable [directed biogas] it would be offsetting any carbon emissions that would occur otherwise,” Scott explained.

Scott also noted that in a port setting, on-site production of gas from biomass isn’t feasible, hence the project’s reliance on directed biogas. “There are not a lot of great other options,” Scott said. “Other technologies require either a lot more space or they are further upstream in the development stage.”

California’s three investor-owned utilities (IOUs) – Pacific Gas and Electric, SCE and San Diego Gas and Electric – oppose the inclusion of plants using directed biogas in the incentive program.

SCE argues that the use of directed biogas isn’t “consistent with the intent of the BioMAT program,” and therefore shouldn’t qualify for the higher pricing afforded to producers in the program. “SCE is continuously contracting with generators to help ensure sufficient clean generation resources; however, SCE also considers the cost its customers are paying for those contracts,” Laffoon Villegas told the Business Journal. “SCE can procure additional renewable resources at prices significantly lower than BioMAT prices.”

But reducing carbon emissions from power generation isn’t the only environmental benefit the plant stands to create, its developers argue. For Toyota, the main appeal of the project comes from its ability to create hydrogen, which the company plans to use in zero-emission trucks and consumer vehicles. In April, Toyota and truck manufacturer Kenworth announced plans to bring 10 hydrogen-fueled trucks to the San Pedro Bay ports, a project that has received financial support in the form of $41 million in cap-and-trade dollars from the California Air Resources Board.

The impact of hydrogen production at FuelCell’s plant would go beyond the 10 initial trucks the project is set to produce, Scott argued. “Developing solutions for renewable hydrogen pathways – especially 100% renewable hydrogen pathways – is very important to us,” he noted. “Hydrogen has the unique opportunity to be scalable and this was one way to demonstrate the scalability of it.” As a result, the success of the project would encourage the replacement of high-emission diesel trucks with hydrogen-powered trucks on a larger scale, he explained.

The Port of Long Beach has expressed its support for the project. In a letter to SCE, the port’s acting director of environmental planning, Matthew Arms, detailed the benefits of the project to the port and surrounding communities, offering to meet with SCE representatives on the issue. So far, Arms told the Business Journal, no meeting has taken place. “I really hope that they can come to some agreeable terms,” Arms said. “We see it as a great step forward and as a partner in the port, a port tenant, taking on a great project that could benefit the environment and the community.”

Currently, the two sides await clarification on the eligibility of directed biogas for the BioMAT program. If the CPUC sides with the investor-owned utilities, plans for the fuel cell power plant would likely be scrapped. “If Edison is ultimately successful in rejecting the project, then there would be no plant built by [FuelCell] on site,” Scott said. “I don’t think it would be economically competitive for them to do so.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story stated that Toyota’s facility at the Port of Long Beach processed 400,000 vehicles per year. The article has been updated to reflect the accurate number of vehicles processed, 200,000.